A Review from a Peer: The Endorsement of Jose Tupaz Jr. for National Artist

- sandylichauco

- Dec 11, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 12, 2025

Throughout Philippine art history, the list of National Artists reflects the country’s key cultural icons. However, a primary source document from May 26, 1984, shared with me by a friend and posted on Facebook by a relative over eight years ago, and transcribed below, reveals a significant gap within this group. The letter, written by the esteemed diplomat and statesman Carlos P. Romulo, is addressed to First Lady Imelda Romualdez Marcos. In it, Romulo passionately and intellectually advocates for recognizing Jose J. Tupaz, Jr., owner of the renowned engraving company "El Oro," as a National Artist.

May 26, 1984

The First Lady and Governor Imelda Romualdez Marcos

Malacañang, Manila

Dear Madam:

The "National Artist" award had been conferred to the nation's leading artist or artisans in the field of music, architecture, dance, sculpture, film, literature, drama and painting. But engraving, a field of sculpture is equally deserving of recognition, and there is only one person who has been consistently outstanding in the area, none other than MR. JOSE J. TUPAZ, JR., of "EL ORO, the nation's artist engraver, since 1957, when our beloved President, the late Ramon Magsaysay "The Guy" conferred upon him the title "Official Engraver of the Republic of the Philippines in recognition for the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP).

The choice of Mr. Tupaz as official engraver was confirmed and ratified by His Excellency, President Ferdinand E. Marcos in 1969, a reaffirmation of his many outstanding contributions in engraving, which raised it as an art, at par with the other fields of art or culture.

Mr. Tupaz had already been conferred several awards and decorations both local and abroad as an artist engraver par excellence, principally, the Republic Cultural Heritage Award in June 12, 1966 for his "creative work in the field of an almost unknown media but a major branch of sculpture, "The Engraver of the Year Award" (1955) of the Business Writers Association of the Philippines (BWAP) and the "Award of Distinction (3rd place) at the 2nd Exposicion Numismatica International de Medalla in 1951 in Madrid, and the 7th Congress of International Federation of Medal Editors in Quiai, Conti, Paris, France in 1957.

I honestly and sincerely believe that it is about time that due recognition be given to Mr. Tupaz, and in his field of engraving, and that as an artist engraver, the nation owes him a debt of gratitude for his selected works of art, and the nation's highest award in art - The National Artist Award.

I have the distinct privilege and honor therefore to recommend that MR. JOSE J. TUPAZ, JR., of "EL ORO" be conferred the "National Artist Award".

Thank you.

Very sincerely yours,

(Signed)CARLOS P. ROMULO

This document is not just a recommendation; it is a vital intervention in defining "fine art" in the Philippines. It questions the institutional boundaries that often separate "sculpture" from "engraving" and emphasizes a legacy that, despite its widespread presence in Philippine heraldry, remains formally unrecognized by the Order of National Artists.

To understand the importance of this letter, it is essential to consider the background of the letter's author. By 1984, General Carlos P. Romulo was not only the Minister of Foreign Affairs but also a National Artist for Literature, having received this honor in 1982. Therefore, this letter serves as a "peer review" of the highest level—one National Artist advocating for the recognition of a contemporary. Romulo’s influence carried significant cultural and political weight. His claim that Tupaz was "equally deserving of recognition" alongside painters and musicians was a strong endorsement of Tupaz’s artistic value, elevating him from the category of "craftsman" to "artist."

Romulo's main argument focuses on reclassifying engraving. From what I understand, the categories for the National Artist Award have traditionally included Music, Dance, Theater, Visual Arts, Literature, Film, and Architecture. Engraving is often considered part of "applied arts" or manufacturing.

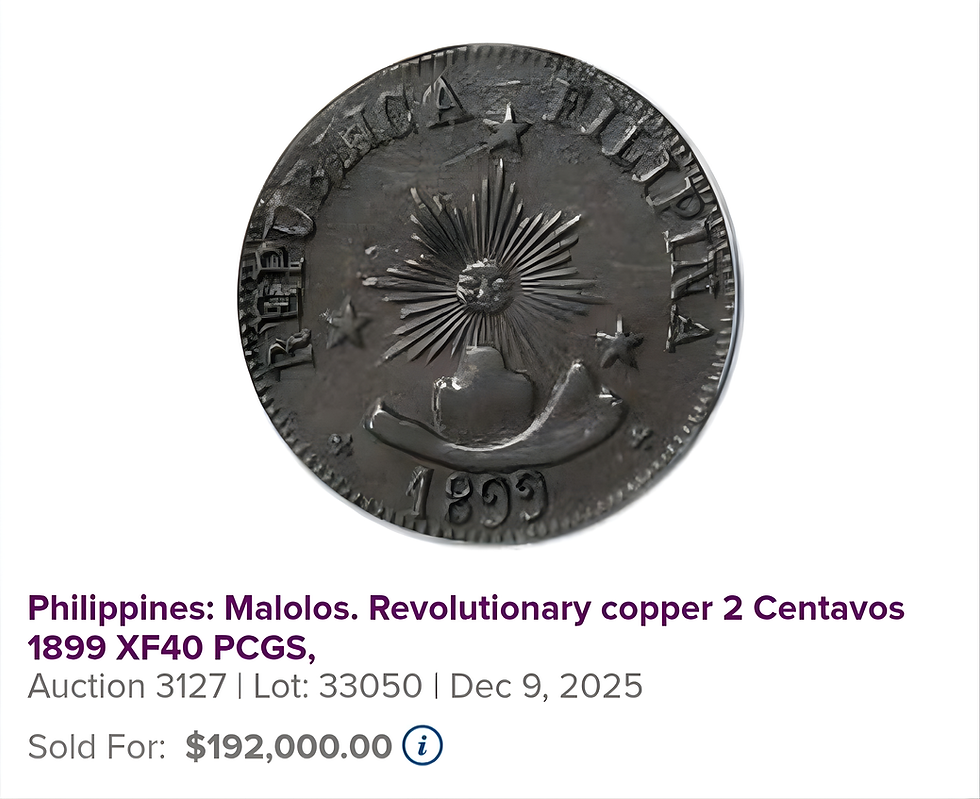

Romulo challenges this oversimplification. He explicitly describes engraving as "a field of sculpture" and "a major branch of sculpture" in his letter. He argues that the medium’s technical requirements and aesthetic output—medals, coinage, and heraldry—demand the same mastery of form, relief, and composition as traditional sculpture. He supports this by citing Tupaz’s international achievements, specifically his victories in Madrid (1951) and Paris (1957). These were not industrial trade shows but art exhibitions (e.g., Exposicion Numismatica International de Medalla), demonstrating that the global art community recognized Tupaz’s work as fine art long before the Philippine government formally recognized it.

The letter outlines the "institutional validation" Tupaz had already obtained, which should have made his National Artist candidacy a mere formality.

State Recognition: He was the "Official Engraver of the Republic" under President Magsaysay (1957) and reaffirmed by President Marcos (1969).

Cultural Heritage: He received the Republic Cultural Heritage Award in 1966. This award is important because, before the National Artist Award was established in 1972, it was the country's highest cultural honor. Many Republic Cultural Heritage awardees (like Amado Hernandez or Nick Joaquin) later became National Artists. Tupaz' holding of this earlier award supports the idea that his exclusion may have been an oversight.

Ubiquity: Through his firm, El Oro, Tupaz created the literal symbols of the Philippine nation—the medals pinned on heroes and the seals of office. His art was not hidden in galleries; it was worn on the chests of the nation's bravest.

Despite this strong recommendation highlights that Jose J. Tupaz, Jr. is not listed on the official roster of National Artists. I believe the significance of this letter lies in revealing a systemic bias in the art world: the hierarchy that favors "pure" arts (painting on canvas, casting bronze statues) over "functional" arts (medallic art, numismatics, engraving). Tupaz should have been recognized not only for his technical skill but also for his contribution to nation-building—a key criterion of the award. By designing and issuing the country's honors system (decorations and service medals), he helped shape the visual representation of Philippine identity. As Romulo eloquently stated, "the nation owes him a debt of gratitude."

This 1984 letter from Carlos P. Romulo serves as validation. While Jose J. Tupaz, Jr. may never have worn the Grand Collar of a National Artist, this document confirms that his peers—the titans of Philippine culture—considered him one of their own. It reminds us that the official canon is never complete, and that some of the nation's most significant artists are those whose work we see, hold, and wear every day, without ever knowing their names.

'

Sources:

Comments