Monumentalizing History in Miniature: The National Artist Case for Figueroa, Tupaz and the Art of the Medal

- sandylichauco

- Dec 12, 2025

- 9 min read

Our recent discovery of Carlos P. Romulo’s 1984 letter advocating for Jose J. Tupaz, Jr., as discussed in a blog we posted a few days ago (https://www.nineteenkopongkopong.com/post/a-review-from-a-peer-the-endorsement-of-jose-tupaz-jr-for-national-artist), strengthens the case for recognizing engraving as a fine art in the Philippines. Romulo’s idea—that engraving is "a major branch of sculpture" deserving of the National Artist Award—is well-supported. But if we accept this idea, we should also acknowledge Melecio Figueroa, who did more than just engrave medals for the state; he engraved the nation's image into the minds of its people. While Tupaz was the "Official Engraver" of the Republic, Figueroa was the "Prince of Filipino Engravers," leaving his mark during the darker and tougher times of Spanish and American colonial rule. If the National Artist Award is about contributing to nation-building and artistic excellence, Figueroa’s "uphill struggle" and enduring legacy make a very strong case.

Jose Tupaz Jr., through his establishment El Oro, cemented his reputation as the leading Filipino medalist and engraver of the mid-20th century by raising the artistic and technical standards of Philippine numismatics and heraldry. He is best known for his extensive portfolio of state

commissions during the "golden years" of Philippine medal craftsmanship—covering the administrations of Presidents Ramon Magsaysay to Ferdinand Marcos—where he served as the official engraver for the Philippine government. His fame largely stems from his expertly crafted presidential inauguration medals, which collectors highly value for their detailed relief and historical significance, and from phis production ofthe country's top military decorations, such as the Philippine Legion of Honor and the Military Merit Medal. Beyond official awards, Tupaz gained international recognition for his commemorative works, especially the 1961 Jose Rizal Centennial medals and the 1963 First Philippine Republic Independence Day Medal, which won prizes at numismatic exhibitions in Madrid and Paris, establishing El Oro as a leader in Philippine metalcraft and engraving excellence.

In stark contrast, Melecio Figueroa (1842-1903) navigated a world where Filipinos were often viewed as second-class citizens. Figueroa was born on May 24, 1892, in Arevalo, Iloilo. He was orphaned early and sent to live with relatives in Sorsogon, where he survived by carving wooden dolls—his talent was his only means of support. Figueroa’s fight was for recognition within the heart of the empire. Sent to Madrid on a scholarship, he enrolled at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando—the same school attended by Luna and Hidalgo. But when his benefactor died, Figueroa did not return home defeated; he supported himself by repairing watches in Madrid, refusing to give up his art. Despite these hardships, he outperformed the colonizers at their own game. He won awards at the Exposición de Bellas Artes in 1875 for his bust of King Alfonso XII and served as a judge at the Exposición de Filipinas in 1887. While the state recognized Tupaz, Figueroa forced the Spanish academy to acknowledge indigenous talent through sheer technical skill.

The strongest argument for Figueroa lies in the ubiquity and symbolism of his work. While the military elite wore Tupaz’s medals and decorations, Figueroa’s work was embraced by the

masses, as evidenced by his most famous “medallic” work. In 1903, the American colonial government held a competition for the new Philippine coinage. Figueroa, a Filipino, won against American designers. His winning design, “the Filipinas,” is perhaps the most iconic numismatic image in our history.

The Image: A Filipina woman (modeled after his daughter, Blanca) with flowing hair, wielding a hammer against an anvil.

The Symbolism: In the background, Mt. Mayon symbolizes the beauty of the land. The act of striking the anvil represents a nation "forging" its own future through labor and industry.

This was not passive portraiture; it was active allegorical sculpture. Known as the "Conant Series," these coins circulated until the 1960s. For more than fifty years, the primary visual

symbol of "Filipinas" among citizens was Figueroa’s engraving. This image was the "award" given to the Filipino people—a visual promise that through industry and labor, the "Pearl of the Orient" would rise. It remains one of the most beautiful coins in numismatic history and a favorite among numismatists and collectors for many years. Coincidentally, the highest-graded USPI One Peso 1906s coin was auctioned a year ago for a record-breaking P9M at Heritage Auctions. The coin came from the Byron Milstead collection, a prolific collector and one of the nicest collectors in this part of the world.

If Jose Tupaz Jr. is the herald of the independent Republic, then Melecio Figueroa is the chronicler of the Philippines' transition from Spanish colony to American territory. His canvas was not cloth, but copper, silver, and gold. His works were not just decorations; they served as historical markers that captured the political and cultural spirit of the late 19th century. While he is best known for his coinage, Figueroa’s technical skill is most evident in his commemorative medals. These were not mass-produced industrial tokens but high-relief miniature sculptures that required the same level of anatomical precision as a life-sized statue.

1. The 1887 Exposición General de Filipinas Medal

The Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas, held in Madrid’s Retiro Park in 1887, was a major colonial exhibition intended to showcase the "products, art, and culture" of the Philippines to Spain. It remains historically controversial for displaying indigenous people as "exhibits," but artistically, it was a success for Filipino painters such as Hidalgo. Figueroa not only attended the exposition but also served as a judge. More importantly, he was commissioned to design the medals awarded to the winning exhibitors. Working with Spanish engraver Juan Bautista Feu, Figueroa helped develop the event's visual identity. The medal served as the physical "Award of Excellence" given to Filipinos who excelled in agriculture, industry, and fine arts. For a Filipino "Indio" to design the prize awarded by Spanish and European judges was a subtle yet powerful challenge to the colonial hierarchy.

2. The Victor Balaguer Medal (1885)

Before the 1887 Exposition, Figueroa already established his reputation in Madrid with this silver masterpiece. Dedicated to Don Victor Balaguer, a prominent Catalan politician, historian,

and the Minister of Overseas Colonies (Ultramar). This was a portrait medal—a genre that requires great skill to accurately capture a likeness in shallow relief. It is now the oldest known signed medal by Figueroa. Its existence indicates that Figueroa was well-connected in high political circles in Madrid and trusted to immortalize the features of the ruling class, a rare privilege for a colonial subject.

3. The 1895 Regional Exposicion de Filipinas

While the 1887 Madrid Exposition marked Figueroa’s debut on the European stage, the 1895 Exposición Regional de Filipinas was his triumphant return home. Held in Manila just a year before the start of the Philippine Revolution, this event was the Spanish colonial government’s last major effort to showcase stability and progress. Once again, the task of immortalizing this event fell to Figueroa’s hands. His work for this exposition differs significantly from his earlier pieces, demonstrating a mature artist working at the peak of his abilities within the colonial capital.

Unlike the 1887 medal, which was a collaboration with Spanish engravers, the 1895 Regional Exposition medal is often credited solely to Figueroa, with his initials "M.F." on both sides. This reflects his undisputed status as the top engraver in the archipelago at that time.

The Obverse: The Boy King and the Regent

The front of the medal shows the busts of the young King Alfonso XIII and his mother, Queen

Regent Maria Cristina, side by side. This required exceptional skill in portraiture. Capturing the likeness of the royal family was a politically sensitive task. Figueroa’s rendition was not only approved but also praised for its accuracy and grace, demonstrating that an "Indio" artist could depict the monarchy with as much dignity as a peninsular Spaniard.

The Reverse: Allegory of Progress

The reverse illustrates a classic scene: a winged female figure (symbolizing Victory or Fame) holding a laurel branch above a seated male figure (symbolizing Industry or the Artisan). This imagery perfectly captures the "uphill struggle" mentioned earlier. The seated man represents the Filipino artisan—working, creating, and awaiting recognition. The winged figure signifies the validation the Exposition (and Figueroa himself) sought to bestow on local talent.

The 1895 Regional Exposition medal is more than a collector’s item; it’s a historical artifact. It depicts Figueroa at a pivotal moment in history, using his chisel to capture the final moments of one empire and to help shape the identity of the next. To ignore this work is to overlook the visual history of the Philippine revolution. These medals further add a crucial layer to the argument for Figueroa’s nomination:

o ‘Consistency Across Regimes’: Figueroa was the definitive visual voice for the Spanish regime (1895), just as he would become for the American regime (1903). He was the constant thread of artistic excellence during the nation's most turbulent transition.

o Home Court Dominance: While his Madrid awards (1887) proved he could compete in Europe, the 1895 medals demonstrated he was the unmatched master in the Philippines. He wasn't just an expatriate success story; he was a local leader in the arts.

o Historical Significance: These medals were awarded in 1895. A year later, the Katipunan would tear up their cedulas, and the Spanish empire would start to fall apart. These medals are among the last artistic tokens of three centuries of Spanish rule—carved by a Filipino patriot who would soon sign the Malolos Constitution.

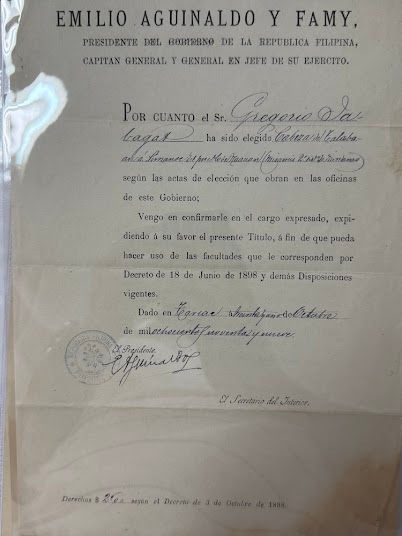

Finally, Figueroa’s case is strengthened by his direct involvement in nation-building, a key requirement for the National Artist Award. He was not just an artist; he was a patriot. Upon returning to the Philippines, he served as a delegate to the Malolos Congress and signed the Malolos Constitution—the first republican constitution in Asia. While Tupaz designed the medals for the Armed Forces, Figueroa helped shape the nation itself. If Tupaz had National Artist awardee (for Literature 1982), Carlos P. Romulo vouching for his entry as a National Artist, it was art historian Fabian de la Rosa who spoke highly of Figueroa, when he was quoted as saying Figueroa was the "only Filipino engraver who had developed the art of engraving from its purely artistic aspect with unsurpassed efficiency."

Carlos P. Romulo was right to champion the art of engraving. But if we are to honor the master of this medium, we must start with the foundation. Melecio Figueroa did not have the luxury of a sovereign state to appoint him "Official Engraver." He had to carve his identity between two empires, Spain and America, and in doing so, he gave the Filipino people a face. If Tupaz is the renowned herald of the Republic, Figueroa is its silent architect. His chisel defined us before we fully defined ourselves. That is the hallmark of a true National Artist!

Monumentalizing History in Miniature

Which brings me to my case for the posthumous awarding of the Order of National Artist to Melecio Figueroa and Jose Tupaz. It is not just an act of nostalgic remembrance but a vital correction to the Philippine art history canon. As this analysis demonstrates, excluding numismatic artistry and medal engraving from mainstream discussions of Philippine sculpture is a significant oversight. Figueroa and Tupaz did more than create currency or insignias; they shaped the country's visual identity through bas-relief, infusing the Filipino spirit into the very metal of its economic and political life.

Figueroa, known as the "Prince of Filipino Engravers," set a standard of classical excellence comparable to European masters of his time. His work on the 1903 Conant series went beyond just creating coins; it established an aesthetic language that defined the American colonial and Commonwealth periods. Likewise, Jose Tupaz linked pre-war traditions with modern governance. He transformed the craft of engraving into a means of preserving national memory, ensuring that the highest honors of the Republic—from the Quezon Service Cross to various Orders of Merit—were awarded with craftsmanship that reflected the nation's dignity.

Therefore, recognizing these two pioneers clearly falls under the responsibilities of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) and the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP). To deny them the title of National Artist is to dismiss the validity of "sculpture in miniature" and to overlook the significant influence of functional art on the collective consciousness.

Ultimately, elevating Melecio Figueroa and Jose Tupaz to the National Artists pantheon would achieve three key goals.

1. Legitimization: It would officially recognize medal art and numismatics as important subfields of Philippine Sculpture.

2. Preservation: It would safeguard the engraver’s distinct technique—the mastery of the burin and die—against the decline brought on by industrial mass production.

3. Integration: It would complete the story of Philippine Art by acknowledging that the nation's history is written not only on canvas and stone but also in gold, silver, and bronze.

By awarding the Order of National Artists to Figueroa and Tupaz, we recognize that their contributions extend beyond technical skill; they embody cultural resilience and innovation. Their works are not just historically significant artifacts but also lasting symbols of Filipino identity that continue to inspire future generations. By honoring these artists, we reaffirm the vital role of numismatic and medallic art in national expression and remembrance.

In my view and hope, it is the responsibility of the cultural authorities to posthumously honor these masters, as their meticulous attention to detail demonstrated that a nation's greatness can indeed be held in the palm of a hand.

Sources:

Melecio Figueroa unfortunately cannot be considered for the title of National Artist. Simply because one of the required provisions in being bestowed the award, is for the recipient to be a "Filipino Citizen" at the end of their life.

Figueroa passed in 1903, there was no Independent Republic of the Philippines then. Also he would have been a US National (not citizen) at that time.

One also thinks, this may be the reason why Anita Magsaysay Ho may never be conferred the designation. This because she died a Canadian Citizen.

Figueroa has a better title anyway, Filipino Gilded Age Master. Also the National Artist title has been tainted by that controversy in 2009. When former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo submitted…