Market Distortion or New Paradigm? Deconstructing the Record-Breaking Sale of the 1899 Malolos Revolutionary Two Centavo Copper

- sandylichauco

- Dec 21, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Dec 21, 2025

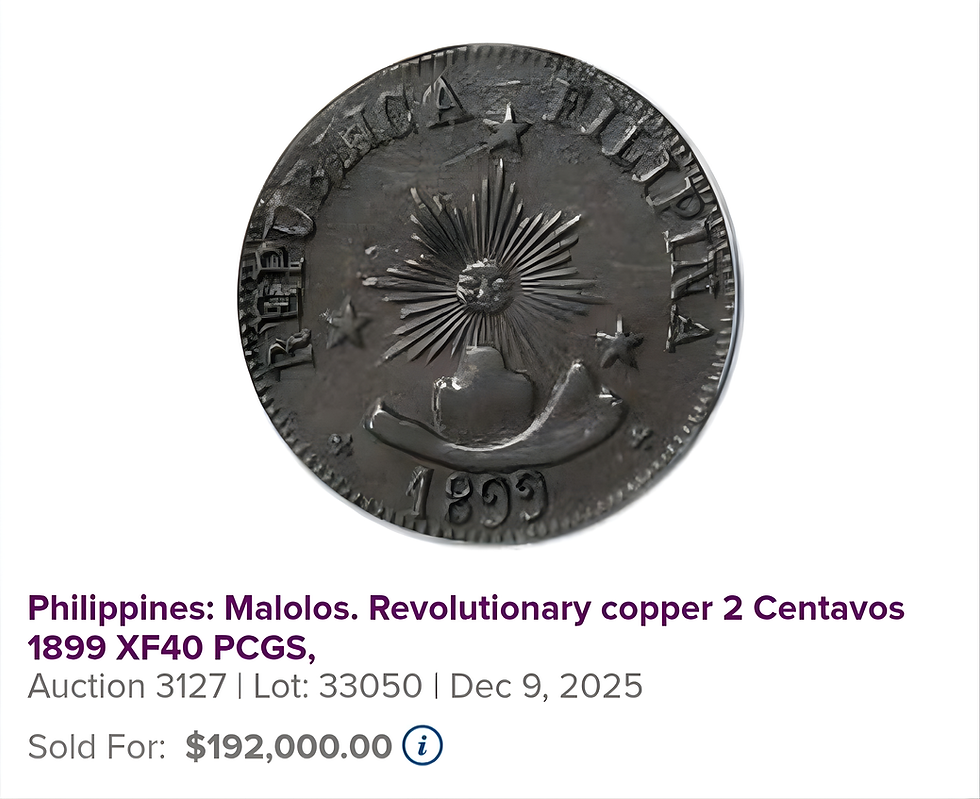

It has been three weeks since the gavel fell at the Heritage auction, sending shockwaves through the Philippine numismatic community. The lot in question—an 1899 Two (2) Centavos Malolos Revolutionary Copper, graded XF40 by PCGS and from the esteemed Mahal Collection—realized a staggering $192,000. This result has not only rewritten the record books but also prompted a serious re-evaluation of value drivers in our market. For the first time, a Philippine revolutionary copper coin has dwarfed the giants of the Spanish and US-Philippine colonial series. To understand the gravity of this sale, we must first contextualize the current hierarchy of Philippine numismatic records. While the figure is cause for celebration of the market’s robustness, a critical analysis suggests this valuation may reflect less intrinsic scarcity and more provenance-driven exuberance. However, first, it is important to examine the coin's history to understand the reason for this record-breaking result.

A Relic of the First Republic: The History of the 1899 Malolos Coinage

To understand why the 1899 Two (2) Centavos Malolos commands such reverence—regardless of current market valuations—one must look beyond the metal to the birth of the Filipino nation. This coin is not merely currency; it is a tangible assertion of sovereignty by the first independent republic in Asia.

The Context: A Nation in Flux

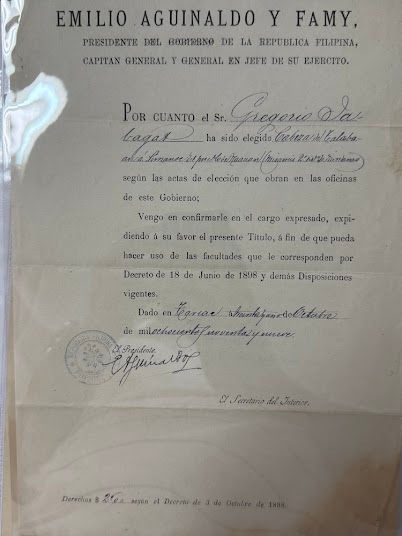

Following the declaration of independence in June 1898 and the convening of the Malolos Congress, the newly formed government under General Emilio Aguinaldo recognized a fundamental truth of statecraft: a legitimate nation must issue its own currency. To replace the Mexican pesos and Spanish colonial coinage that dominated local commerce, the revolutionary government established the Malolos Arsenal.

The Production: Minted in the Crossfire

The 2 Centavos copper coin was struck under chaotic conditions. As the Philippine-American War loomed and eventually erupted in February 1899, the revolutionary army converted the Malolos convent into an arsenal. Amid the production of ammunition and the repair of Mauser rifles, a small minting operation was established. Historical accounts suggest that the raw materials were often scavenged—copper sheets, wires, and even spent cartridge cases collected from the battlefield. The dies were engraved by local artisans, resulting in a primitive yet powerful aesthetic.

The Design

The coin's design reflects the aspirations of the Katipunan and the new Republic.

Obverse: Typically features the inscription "Republica Filipina" surrounding a sun with rays—a direct nod to the revolutionary flag and the dawn of liberty.

Reverse: Displays the denomination and the year "1899," often accompanied by the word "Libertad" (Liberty).

The Scarcity

The rarity of the 1899 2 Centavos is a direct consequence of history. The Malolos Republic was short-lived. By March 31, 1899, American forces under General Arthur MacArthur Jr. captured Malolos, the fledgling republic's capital. The minting facilities were seized or destroyed, and production of these coins ceased almost as soon as it began. Many of the coins that had entered circulation were likely confiscated and melted down by the American colonial administration to suppress Filipino nationalism, or lost amid the war's turmoil. Today, the few surviving examples—such as the XF40 specimen from the Mahal Collection—serve as rare metallic witnesses to the Philippines' defiant struggle for independence.

Now enough of history, back to the auction results.

The New Hierarchy: Top 6 Philippine Coins by Auction Result

To understand the magnitude of this sale, one must view it in the context of the new numismatic order. The following data shows the current apex of Philippine auction records as of late 2025:

Valuation vs. Rarity: The Provenance Premium

This analysis holds that the 1899 Malolos 2 Centavos is significantly overvalued relative to its peers on the Top 6 list. While the coin is undeniably rare, it does not possess the "uniqueness" often required to justify such a commanding price point. It is imperative to determine whether the $192,000 valuation of the Malolos 2 Centavos reflects intrinsic rarity or a temporary market distortion. We believe the coin is significantly overvalued, a phenomenon that sometimes occurs in auction settings.

We are aware of at least two or three other genuine specimens currently held in private collections in the Philippines. In fact, we had the honor and privilege of handling one of these coins for a while. These are authenticated examples, distinct from the spurious "unverifiable" pieces that plague the market. Contrast this with the coins it has surpassed: the 8 Escudos with the Ysabel II countermark and the Peruana 2 Reales with the Ferdinand VII countermark are virtually unique in their specific host-countermark configurations. Even the 1906-S USPI Peso in MS63 has only one known peer of equal grade in private hands, whereas the No. 5 on the list is the subject of a short Facebook piece we wrote.(https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1BnGtKdYJ3/)

The driving force behind the $192,000 result appears to be the "Mahal Collection" pedigree (which we believe traces back to the legendary Rosenthal Collection). The market seems to have priced the story rather than the asset, creating a "perfect storm" of hype. While provenance is a legitimate value-add, it typically does not sustain a valuation that exceeds the item's fundamental scarcity—especially when other genuine samples exist in the shadows.

The "Cobra Effect": The Threat of the Den of Thieves

Perhaps the most concerning implication of this record-breaking sale is the behavioral response it will inevitably trigger in the market’s illicit underbelly. We are facing a scenario dangerously analogous to the "Barilla Incident" of 2022. When auction prices for 18th-century Barilla coppers reached all-time highs, the market did not respond with discovery; it responded with fabrication and manufacturing. The so-called "Den of Thieves" flooded the hobby with forgeries. The influx was so severe that Third-Party Graders (TPGs) eventually ceased slabbing Barillas altogether, declaring many "Authenticity Unverifiable" due to the contamination of the population report; of course, they will never admit it.

A $192,000 benchmark for a copper coin creates a strong economic incentive for these actors. We can anticipate a sudden "manufacture" of Malolos coppers in the coming months, designed to prey on new capital chasing the latest hype. This is the darker side of numismatic inflation: as prices soar, it triggers "evil schemes" that threaten the integrity of the hobby.

The sale of the 1899 Malolos copper is a double-edged sword. It brings prestige to Philippine numismatics, yet it signals a dangerous disconnect between price and rarity. Collectors must remain vigilant, distinguishing between a coin’s fame and its actual population. If we fail to exercise this discernment, we risk surrendering the market to the very thieves who seek to dilute it, ultimately sending the hobby "to the dogs."

Sources:

https://usa.inquirer.net/145631/the-collapse-of-malolos-march-31-1899

Basso, Aldo P. (1968). Coins, Medals and Tokens of the Philippines. Chenby Publishers.

Legarda, Angelita G. (1976). Piloncitos to Pesos: A Brief History of Coinage in the Philippines. Bancom Development Corp.

Perez, Gilbert S. (1921). The Mint of the Philippine Islands. American Numismatic Society.

Agoncillo, Teodoro A. (1960). Malolos: The Crisis of the Republic. University of the Philippines.

Majul, Cesar Adib. (1967). The Political and Constitutional Ideas of the Philippine Revolution. University of the Philippines Press.

Stack's Bowers Galleries & Heritage Auctions (Archive). The Mahal Collection of Spanish and US Philippines Coins.

PCGS & NGC Population Reports.

Comments